May 2022: yet again, tons of plakar stuff

Table of Contents

TL;DR:

tons of plakar work, most notably on indexes, performances, clone & sync and fuse.

Code-unrelated work#

I’ll start with code unrelated work !

I’ve picked up playing electric guitar and metal after years of playing mostly jazz and classical on nylon-string guitars. After a couple weeks of enduring finger pain while re-conditionning myself to playing on steel strings, I decided to give myself a challenge and learn some shredding, a topic I conveniently always dodged :-)

I took this track which I absolutely love, Hyunsoo Lee’s adaptation of Bach’s Air on G string, and started practicing because it uses some techniques I’m not too good with such as sweeping and fast runs:

I still have a lot of work to do, particularly when playing at full speed, but I’m very happy with the progress I’m making on this so I’m sharing :-)

I’m also working on a couple other covers, I’ll post when I’m happy with them too.

Split indexes#

As a follow up to refactor from previous month, I continued to work on improving the data structures used by plakar.

Just as I had split Index and Metadata,

I have now also split the Index and Filesystem view of a snapshot so a plakar snapshot now has three indexes:

Metadata contains, well, metadatas for lookups of general purpose informations regarding a snapshot,

Index contains everything necessary to figure out the structure of files and what’s needed to reconstruct it,

and Filesystem contains everything necessary to figure otu the structure of snapshotted filesystems.

Basically,

if you want to know the size of a snapshot,

Metadata is the only index necessary.

If you want to figure out which chunks constitute /etc/passwd,

Index is the only index necessary.

If you want to figure out which files are in /etc,

or what were the permissions of /etc/passwd,

Filesystem is the only index necessary.

As most command only rely on one of these simultaneously,

this speeds up things as commands do not have to wait for the three indexes to be fetched before being able to work.

Not all commands benefit from this split yet as they need to be adapted, but this will be a transparent change where some commands get a performance boost out of nowhere as I reimplement them properly.

Binary indexes#

Up until last month,

I had used json as the storage format for indexes,

and there were two reasons for that:

First, it allowed me to not worry too much about serialization.

I could simply json-marshal the Metadata, Index and Filesystem indexes which would generate a set of dictionnaries,

both usable with a simple json-unmarshal and no state “rebuilding” (that’s converting from a disk format to different structures in memory, imposing a conversion cost).

Then, it also helped me debug things as I could always use an unencrypted plakar and rely on the jq command to read the indexes,

check that they contained the expected data and generally play with them with json-aware tools.

The problem is that json serialization and deserialization comes at a cost, both in terms of space consumption as it’s far from being a very compact format and snapshot may contain dozens of thousands of objects leading to a loooooooot of waste, but also in terms of performances as the format itself is more costly to serialize and deserialize than binary formats.

I have ideas where I want to go with serialization of indexes but a good first step was to switch from json to a decent binary format, one that would be more efficient to start with but which would also allow me to ensure that nothing relied on json anymore.

After some investigations,

I ran into msgpack which seemed to be a good candidate,

was already fairly popular in other projects,

but more importantly didn’t require too much work to plug in.

It claimed to provide much better performances than json serialization,

which I didn’t observe myself,

but helped cut the index sizes considerably as in average it shrank them by 25% and up to 50% in some of my tests.

Compact indexes#

With work being done to split indexes and switch them to a binary format, I decided to stay focused on index improvements and trying to make them as compact as I could.

The reason is that indexes weight “two” sizes: the storage size, when they’re written to disk, and the runtime size, when they’re loaded into memory. Both these sizes have benefits being optimized, the former allowing faster deserialization, the latter providing a smaller footprint and faster serialization.

In an ideal world, the data structures stored on disk are compressed to the smallest possible size to reduce loading time, but the data structures loaded in memory should be as close as possible to their disk counterparts to avoid conversion costs. The optimal case would be that indexes are compressed in such a way that they can be loaded compressed in memory, and usable without decompressing them.

So first of all,

I did a pass to compress data types as I knew there would be an instant gain from a (seemingly) simple change.

The project uses uuid (16 bytes) and sha256 sums (32 bytes) all over the place,

but for convenience I used human-readable representations of these formats,

that is 36-bytes strings for uuid and 64-bytes strings for sha256.

These landed in many data structures in their human-readable representation,

meaning that 20 bytes were wasted every time a uuid was stored and 32 bytes were wasted every time a sum was stored.

This doesn’t look much but that’s until you realize that most of what’s stored in the indexes are mappings that associate sums to each others,

so when a snapshot contains dozens of thousands of files the waste builds up:

gain was already quite nice at this point as it halved the size of indexes on the snapshots of my work directory.

Then,

I did another pass to compress index size further.

As I wrote above, most of what’s stored in indexes are mappings that associate sums to each others,

and to achieve that there are several mappings and reverse mappings which tend to repeat the same information in reverse order.

To answer questions such as what are the chunks in object X ? or what objects contain the chunk Y ?,

you need to have a mapping associating the checksum of object X to a serie of chunk checksums,

but also to have a mapping associating the checksum of chunk Y to a serie of object checksums.

This means that a ton of 32-byte checksums are repeated duplicated and appear at least twice in indexes.

By using a symbol table and an indirection,

it is possible to reduce the index sizes by replacing 32-byte checksums with a much smaller and unique 8-byte identifier.

Because each checksums appear at least twice,

the index shrinks by roughly 50% in the worse case and is effectively compressed in memory.

at the cost of a O(1) indirection in the symbol table.

These were cumulative so by the end of this round of optimizations, indexes were about 4x times smaller than what they were to start with, and because of how the compression works it also means they don’t grow as much as they used to.

I still have ideas to improve further on indexes compression, but at this point I’m satisfied with what I have and the current trade-off ratio between size and convenience. I know I have some improvement margin still but will only use it if absolutely necessary.

Display index, filesystem and metadata#

Because the changes above made it harder to investigate the content of indexes, as they are no longer stored in a human-readable format, I implemented a helper command to json-dump their content allowing to inspect them with:

% plakar info -metadata 39| jq .|grep IndexID

"IndexID": "39d10f01-992f-471c-88f7-c730b003c8b6",

% plakar info -filesystem 39| jq .| grep cmd_pull.go

"cmd_pull.go": {

"Name": "cmd_pull.go",

"/Users/gilles/wip/github.com/poolpOrg/plakar/cmd/plakar/cmd_pull.go": 16,

% plakar info -index 39 | jq . | less

[...]

"12": {

"Start": 0,

"Length": 8423

},

"13": {

"Start": 0,

"Length": 1054

},

"14": {

"Start": 0,

"Length": 1889

},

[...]

They will load the binary format of indexes and dump them to stdout after encoding them to json.

It’s a bit hard to write about this feature,

so feel free to look at the output of these commands by yourself.

Performances, profiling and cache#

I did something I had not done before: try an alternate solution to plakar and compare runtime execution timings.

I expected plakar to be a bit slower because it lacks maturity and I didn’t spend much time optimizing yet, but I intuitively thought it would be roughly 25% slower with an easily achievable margin of improvement.

I installed restic and after a few minutes of reading documentation to figure out the command line interface,

I ran a couple snapshots… and was left speechless.

It was considerably faster, not by 25% but more like 25x faster.

To be more precise,

the initial snapshot was about 25% faster than with plakar,

which was what I expected it to be…

but subsequent snapshots took only a couple seconds when they could take a minute with plakar.

I honestly didn’t think they could be so fast.

After a few seconds of contemplation and investigation to make sure that I didn’t miss something on the command line and that it actually did the subsequent snapshots, I decided to do a first pass of optimization right away to bring my plakar timings at least in the 25% range. I didn’t want to work on optimization right away, because it would be premature with all of the changes still happening, and I don’t want them to go in the way of design at this point… but I also didn’t want to create a situation were the design would lock me too far from alternatives performance-wise. I mainly needed reassurance that suboptimal performances remained in the realm of achievable improvements when I’ll be tackling them.

I wrote a runtime profiling mechanism,

that you can enable with the -profiling,

and which allowed me to track what were the main areas that needed improvements:

% plakar -profiling push

[profiling]: snapshot.PutMetadata: calls=1, min=325.25µs, avg=325.25µs, max=325.25µs, total=325.25µs

[profiling]: cache.Commit: calls=1, min=270.75µs, avg=270.75µs, max=270.75µs, total=270.75µs

[profiling]: cache.New: calls=1, min=66.272166ms, avg=66.272166ms, max=66.272166ms, total=66.272166ms

[profiling]: snapshot.GetCachedObject: calls=26, min=208.584µs, avg=864.285µs, max=1.508667ms, total=22.471418ms

[profiling]: snapshot.PutIndex: calls=1, min=1.446208ms, avg=1.446208ms, max=1.446208ms, total=1.446208ms

[profiling]: storage.tx.PutIndex: calls=1, min=141.375µs, avg=141.375µs, max=141.375µs, total=141.375µs

[profiling]: storage.tx.PutMetadata: calls=1, min=111.917µs, avg=111.917µs, max=111.917µs, total=111.917µs

[profiling]: storage.Close: calls=1, min=83ns, avg=83ns, max=83ns, total=83ns

[profiling]: storage.CheckChunk: calls=114, min=4.459µs, avg=8.217µs, max=44.708µs, total=936.743µs

[profiling]: snapshot.CheckChunk: calls=114, min=5.125µs, avg=9.433µs, max=79.417µs, total=1.075417ms

[profiling]: snapshot.CheckObject: calls=26, min=6.291µs, avg=10.828µs, max=46.709µs, total=281.541µs

[profiling]: snapshot.Create: calls=1, min=1.63425ms, avg=1.63425ms, max=1.63425ms, total=1.63425ms

[profiling]: storage.GetObject: calls=26, min=5.583µs, avg=9.753µs, max=44.709µs, total=253.584µs

[profiling]: cache.PutFilesystem: calls=1, min=46.542µs, avg=46.542µs, max=46.542µs, total=46.542µs

[profiling]: storage.tx.PutFilesystem: calls=1, min=154.917µs, avg=154.917µs, max=154.917µs, total=154.917µs

[profiling]: snapshot.PutFilesystem: calls=1, min=1.157125ms, avg=1.157125ms, max=1.157125ms, total=1.157125ms

[profiling]: cache.Create: calls=1, min=12.5µs, avg=12.5µs, max=12.5µs, total=12.5µs

[profiling]: storage.Open: calls=1, min=131.042µs, avg=131.042µs, max=131.042µs, total=131.042µs

[profiling]: storage.Transaction: calls=1, min=1.625625ms, avg=1.625625ms, max=1.625625ms, total=1.625625ms

[profiling]: cache.PutMetadata: calls=1, min=12.667µs, avg=12.667µs, max=12.667µs, total=12.667µs

[profiling]: snapshot.Commit: calls=1, min=3.517208ms, avg=3.517208ms, max=3.517208ms, total=3.517208ms

[profiling]: cache.GetPath: calls=26, min=175.792µs, avg=778.532µs, max=1.490375ms, total=20.241836ms

[profiling]: cache.PutIndex: calls=1, min=113.416µs, avg=113.416µs, max=113.416µs, total=113.416µs

[profiling]: storage.tx.Commit: calls=1, min=132.042µs, avg=132.042µs, max=132.042µs, total=132.042µs

%

This made me realize that this very high performance gap was caused by a major difference in what it did compared to restic.

It attempted to maintain repository consistency with every operation,

using complex sequences of operations to maintain correct reference counts,

ensuring that objects were deleted as soon as they were no longer referenced or when a push was aborted,

etc… while restic didn’t take care of that with every operation but used a prune command to do the cleanup.

I really thought it would be neat to keep the repository consistency the way plakar did, but it became obvious that the cost was too prohibitive and no amount of optimizations I could think of would counterweight the cost of this. All operations were made more complex and the cost of consistency was paid with every call, when restic benefited from simpler operations and the cost of consistency was paid only when actually requested.

I backtracked on my ideas and reimplemented plakar’s push using a much simpler strategy,

removing all attempts at playing hard-links and reference counts games to track and cleanup,

but implementing a cleanup operation like restic did.

This immediately brought a huge improvement as plakar remained in the range of 25% for the first push (with some gain though), but immediately fell to the same performances as restic for subsequent pushes. This looks promising because while it has roughly the same timings, unlike restic, plakar uses compression by default and didn’t go through actual optimization yet. This means that performances will likely put it below restic in terms of push times, while repository consumption is already much better when snapshots are compressible. I played a lot with pushing my ~2GB work directory and for the same push time, it would weight ~2GB on restic and only 350MB on plakar.

While I was there, I had a look at the repository structure by poking at the created directories and realized that despite a few differences both were very, very, very close. This gave me confidence that I was not completely off with how I tackled this project :-)

The profiler also helped me realize that there was a bug in the implementation of the local cache. It is implemented using SQLite and I didn’t create the proper indexes, which caused cache accesses to be very costly and negated the benefits of using one as soon as there were a lot of data in it. After fixing, things were much better but I came to the conclusion that SQLite was not the proper tool for my problem, what I really need is a very simple key-value database. I temporarily replaced SQLite with LevelDB for the sake experimenting, but am not too happy as it imposes a lock that makes the cache unusable for reads when a push is in progress. For the time being I made it so the cache is skipped while a push is in progress, I’ll be looking at a different solution that allows reads of older versions of the data when a write is in progress.

Parallelized pull#

The plakar pull operation was not parallelized so while a push could benefit from multiple cores,

pull would restore snapshot content sequentially and one file at at time.

I rewrote it so that it would both take advantage of the snapshot Reader interface I wrote about last month, simplifying code, but also so that it could parallelize restoring and speed things up.

There are other things that can be done to speed up things, like not restoring files which are already there in their last version in the target directory, or looking at stat structure to figure out if some files are hard links to others. Work still needs to be done but it’s already a better version so… meh, no rush.

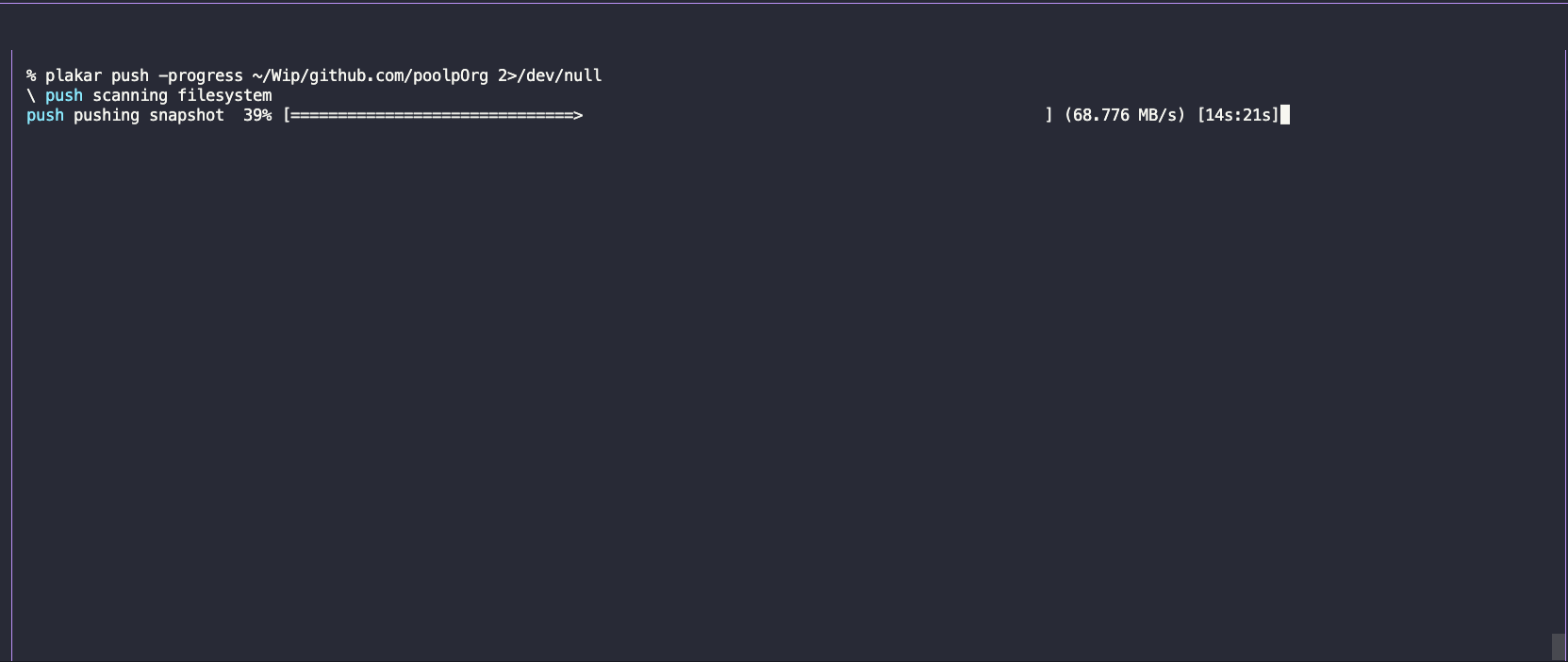

Added a progress bar#

That’s a minor change but one that I really wanted to do and which someone asked me for, prompting me to start working on it.

I implemented the -progress option for plakar push, plakar pull and plakar check,

but I’m not too happy with the way I achieved it.

I’ll revisit later but thought I’d leave it as is for now as it’s still more helpful than not having it.

Reworked clone and sync#

OK, this is by far the most interesting feature in my opinion.

The goal of plakar clone is to create an exact copy of an existing repository,

sharing its repository ID and configuration,

including encryption key.

The goal of plakar sync is to synchronize two repositories by transfering the chunks and objects that are missing in the target repository,

effectively making an exact copy of a snapshot available in a different repository.

I had already implemented plakar clone and plakar sync but they both had shortcomings.

First, they both only supported working with local repositories, ones available on the local filesystem.

Then, sync only supported synchronizing to clone repositories or between unencrypted repositories,

but it didn’t support synchronizing an unencrypted repository with an encrypted one for example.

This was nice already but what I really wanted was for this to work regardless of where a repository is,

and regardless of the configuration of both repositories.

I reworked both commands so that they know support working with arbitrary repositories, and doing the necessary work so there’s no issue when synchronizing repositories not sharing the same configuration.

Why is this the most interesting feature in my opinion ?

Well what I really want with backups is the ability to have them at multiple locations, preferably in different regions. I’ve already lost a few servers at cheap hosts where no disk recovery was offered, and I know of at least one DC that burnt and lost data of all local servers in the process, killing backups that were located on different machines of the same DC. I want to be able to spread backups at multiple locations but I don’t want to have to think too hard about that.

Furthermore, I’m not necessarily interested in having ALL backups encrypted, nor synchronized at the same rate. For instance, I like having backups on my local machine readily available in case I mistakenly trash something, I like having unencrypted backups on my NAS at home in case a machine is unrecoverable, but I’d also like having off-site encrypted backups at one or two cheap hosts in case there was a fire at home and I lost everything. Not all these backups need to happen at the same frequency and I don’t want to have complex strategies here and there, depending on the machine. I can do that with several solutions and a bunch of scripting, but I’ve been there, done that, and it was never fun.

What clone and sync allow me to do is to have exactly what I described in just a few commands,

I can create an unencrypted repository on my laptop:

% plakar on ~/plakar create -no-encryption

Then create a clone on my NAS:

% plakar on ~/plakar clone to ssh://nas.poolp.org

Both repositories are absolutely identical at this point.

My laptop can do a plakar push multiple times a day from a cron,

then every few hours I can synchronize both repositories:

% plakar on ~/plakar sync to ssh://nas.poolp.org

which brings the NAS repository up-to-date with the local repository. I could also synchronize the other way. Say I had multiple machines pushing to the NAS and I wanted my local repository to grab all snapshots, then I’d just:

% plakar on ~/plakar sync from ssh://nas.poolp.org

which brings the local repository up-to-date with the NAS repository. Just like I could clone the NAS repository to bring back an exact copy if I had reinstalled my machine:

% plakar on ~/plakar clone from ssh://nas.poolp.org

But where I find it very useful is that I could create encrypted repositories remotely:

% plakar on ssh://backups.poolp.org create

password:

and synchronize either my NAS or laptop with them:

% plakar on ~/plakar sync to ssh://backups.poolp.org

password:

% plakar on ssh://nas.local sync to ssh://backups.poolp.org

password:

The -keyfile option can be provided to point to a file containing the password so it doesn’t need to be typed,

and allows calling sync from a cron job.

With all of this, it makes it trivial to have multi-site backups all synchronized one with another at different rates.

Reworked snapshot Reader#

Last month, I wrote about how I implemented a snapshot Reader interface and how it helped unlock features and simplify code.

The next feature I’ll write about required me to rework the Reader interface.

A Reader interface is one that allows a Read() operation,

but I really needed a ReadSeekCloser interface,

one that allows Read(), Close() and more importantly Seek() so that I can move the read cursor to arbitrary locations in a stream.

I wrote the interface to implement Seek() on an object so that it would locate the appropriate chunk and maintain an offset to point at the proper position.

This didn’t take too long as I did it in an hour or so,

but it was painful and I lost my soul in the process.

FUSE proof-of-concept#

FUSE is a “Filesystem in USEerspace” mechanism which allows creating mountpoints that expose informations as if they were files on the filesystem. It’s not available on all systems, but when it is, fun stuff are available to play with.

I implemented experimental FUSE support in plakar, making it possible to mount a repository on the filesystem and browse it as if all snapshots had been restored there.

What this means is that I can do:

% plakar on ssh://nas.local mount /mnt/nas

Then I can browse just as if all the repository had been restored below /mnt/nas:

% ls -l /mnt/nas

total 5012576

drwx------ 1 gilles staff 41865948 22 May 22:21 94c815c7-15c6-4a8a-af3a-a83ca620fb55

drwx------ 1 gilles staff 41865948 22 May 22:22 a961b301-e331-4fd1-859e-7ae1d6fca17f

drwx------ 1 gilles staff 2482699293 22 May 22:22 ade656c9-56e7-4e84-b90f-90b3826b08e2

% cd /mnt/nas/94c815c7-15c6-4a8a-af3a-a83ca620fb5

% ls

Users

% cd Users/gilles/Wip/github.com/poolpOrg/plakar/cmd/plakar

% ls -l

total 51216

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 1426 7 May 13:58 cmd_browser.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 2274 11 May 21:53 cmd_cat.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 1748 6 May 23:31 cmd_check.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 1930 10 May 09:09 cmd_checksum.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 1973 6 May 23:31 cmd_cleanup.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 4590 6 May 23:31 cmd_clone.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 2637 6 May 23:31 cmd_create.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 7124 6 May 23:31 cmd_diff.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 2582 6 May 23:31 cmd_exec.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 2818 6 May 23:31 cmd_find.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 8423 6 May 23:31 cmd_info.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 1889 6 May 23:31 cmd_keep.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 7776 6 May 23:31 cmd_ls.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 1784 7 May 13:55 cmd_mount.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 2393 6 May 23:31 cmd_pull.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 1992 6 May 23:31 cmd_push.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 1679 6 May 23:31 cmd_rm.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 1228 6 May 23:31 cmd_server.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 1684 6 May 23:31 cmd_shell.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 1054 6 May 23:31 cmd_stdio.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 5993 6 May 23:31 cmd_sync.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 3096 6 May 23:31 cmd_tarball.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 1147 6 May 23:31 cmd_version.go

-rwxr-xr-x 1 gilles staff 26080594 12 May 23:14 plakar

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 7562 8 May 21:59 plakar.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 gilles staff 9113 6 May 23:31 utils.go

% cat cmd_version.go

/*

* Copyright (c) 2021 Gilles Chehade <gilles@poolp.org>

*

* Permission to use, copy, modify, and distribute this software for any

* purpose with or without fee is hereby granted, provided that the above

* copyright notice and this permission notice appear in all copies.

*

* THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED "AS IS" AND THE AUTHOR DISCLAIMS ALL WARRANTIES

* WITH REGARD TO THIS SOFTWARE INCLUDING ALL IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF

* MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHOR BE LIABLE FOR

* ANY SPECIAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES OR ANY DAMAGES

* WHATSOEVER RESULTING FROM LOSS OF USE, DATA OR PROFITS, WHETHER IN AN

* ACTION OF CONTRACT, NEGLIGENCE OR OTHER TORTIOUS ACTION, ARISING OUT OF

* OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE USE OR PERFORMANCE OF THIS SOFTWARE.

*/

package main

import (

"flag"

"fmt"

"github.com/poolpOrg/plakar/storage"

)

const VERSION = "0.0.1"

func init() {

registerCommand("version", cmd_version)

}

func cmd_version(ctx Plakar, repository *storage.Repository, args []string) int {

flags := flag.NewFlagSet("version", flag.ExitOnError)

flags.Parse(args)

fmt.Println(VERSION)

return 0

}

%

Note that despite cat showing the content of a file here,

files aren’t really on the filesystem but streamed from the repository using the ReadCloseSeeker interface.

As such,

even though I can browse all the snapshots of the repository and access any file content,

they don’t consume disk space locally,

my 256GB laptop could very well mount a repository storing far more than that and allow me to browse and cat any file.

Also note that I mounted a remote repository located at ssh://nas.local which could very well be encrypted as well,

this would work just as fine and transparently.

This is experimental as I had no prior experience playing with FUSE drivers,

there can be a few glitches here and there,

I fixed all the ones I found but still.

Conditional builds#

I added support for conditional builds.

Experimental FUSE support only works on Linux and macOS as far as I know, and doesn’t work for sure on OpenBSD for reasons that I’ve started investigating but which are beyond plakar, so I wanted to make sure that I could still build plakar with the experimental feature removed where it was known not to work… rather than break the entire build.

While at it, the browser feature prevented plakar from building on older Go version, such as the one shipped on some Ubuntu machines I administer for friends. I made sure that this conditionally built depending on the version of Go.

Full text search experiment#

I quickly experimented with FTS in plakar, allowing me to search for all snapshots and files containing a particular content:

% plakar search PutIndex

9 matches, showing 1 through 9, took 80.125µs

1. 46a6777c-8326-48e8-bc8e-4ebfc46c36b4:/Users/gilles/wip/github.com/poolpOrg/plakar/storage/storage.go (0.406516)

2. 46a6777c-8326-48e8-bc8e-4ebfc46c36b4:/Users/gilles/wip/github.com/poolpOrg/plakar/cache/cache.go (0.362482)

3. 46a6777c-8326-48e8-bc8e-4ebfc46c36b4:/Users/gilles/wip/github.com/poolpOrg/plakar/network/server.go (0.277187)

4. 46a6777c-8326-48e8-bc8e-4ebfc46c36b4:/Users/gilles/wip/github.com/poolpOrg/plakar/snapshot/snapshot.go (0.264234)

5. 46a6777c-8326-48e8-bc8e-4ebfc46c36b4:/Users/gilles/wip/github.com/poolpOrg/plakar/storage/client/client.go (0.262951)

6. 46a6777c-8326-48e8-bc8e-4ebfc46c36b4:/Users/gilles/wip/github.com/poolpOrg/plakar/storage/database/database.go (0.254370)

7. 46a6777c-8326-48e8-bc8e-4ebfc46c36b4:/Users/gilles/wip/github.com/poolpOrg/plakar/storage/fs/fs.go (0.238110)

8. 46a6777c-8326-48e8-bc8e-4ebfc46c36b4:/Users/gilles/wip/github.com/poolpOrg/poolp.org/content/posts/2021-10-01/index.md (0.211895)

9. 46a6777c-8326-48e8-bc8e-4ebfc46c36b4:/Users/gilles/wip/github.com/poolpOrg/poolp.org/docs/posts/2021-10-26/october-2021-mostly-plakar/index.html (0.143937)

% plakar pull 46a6777c:/Users/gilles/wip/github.com/poolpOrg/plakar/storage/storage.go

% ls Users/gilles/wip/github.com/poolpOrg/plakar/storage/storage.go

storage.go

%

This was not committed and I have no plans to commit it for the time being, a lot of work still needs to be done before I focus on such features, but it shows how plakar can be improved in ways that my current rsync/tar backups will never match.

S3 experiment#

I also did a small experiment writing an s3 backend for plakar,

allowing it to store repositories on Amazon s3 or on a minio server.

I’m not too comfortable with the API as I never used s3 before, surely I’m not using it correctly, but someone asked me if this would be supported and so I gave it a try.

After about half an hour, I had a plakar repository hosted on a local s3:

% plakar on s3://minioadmin:minioadmin@localhost:9000/my-s3-plakar create -no-encryption

% plakar on s3://minioadmin:minioadmin@localhost:9000/my-s3-plakar push /private/etc 2>/dev/null

% plakar on s3://minioadmin:minioadmin@localhost:9000/my-s3-plakar ls

2022-05-08T21:19:14Z 21388086 3.1 MB 0s /private/etc

% plakar on s3://minioadmin:minioadmin@localhost:9000/my-s3-plakar ls 21:/private/etc/passwd

2022-03-26T07:21:13Z -rw-r--r-- root wheel 7.9 kB passwd

% plakar on s3://minioadmin:minioadmin@localhost:9000/my-s3-plakar cat 21:/private/etc/passwd | tail -3

_darwindaemon:*:284:284:Darwin Daemon:/var/db/darwindaemon:/usr/bin/false

_notification_proxy:*:285:285:Notification Proxy:/var/empty:/usr/bin/false

_oahd:*:441:441:OAH Daemon:/var/empty:/usr/bin/false

%

This will likely need more work but it was a successful proof of concept :-)

What’s next ?#

Next is a couple months of rest.

I’ll be marrying at the end of June and there are still a lot of things to do, I doubt I’ll find much spare time to write code this month… just as I think the month of July will be needed to recover as a wedding is a lot to deal with for someone with an anxiety disorder :-)

Stay tuned, I’ll post as soon as I resume my work !